Description:

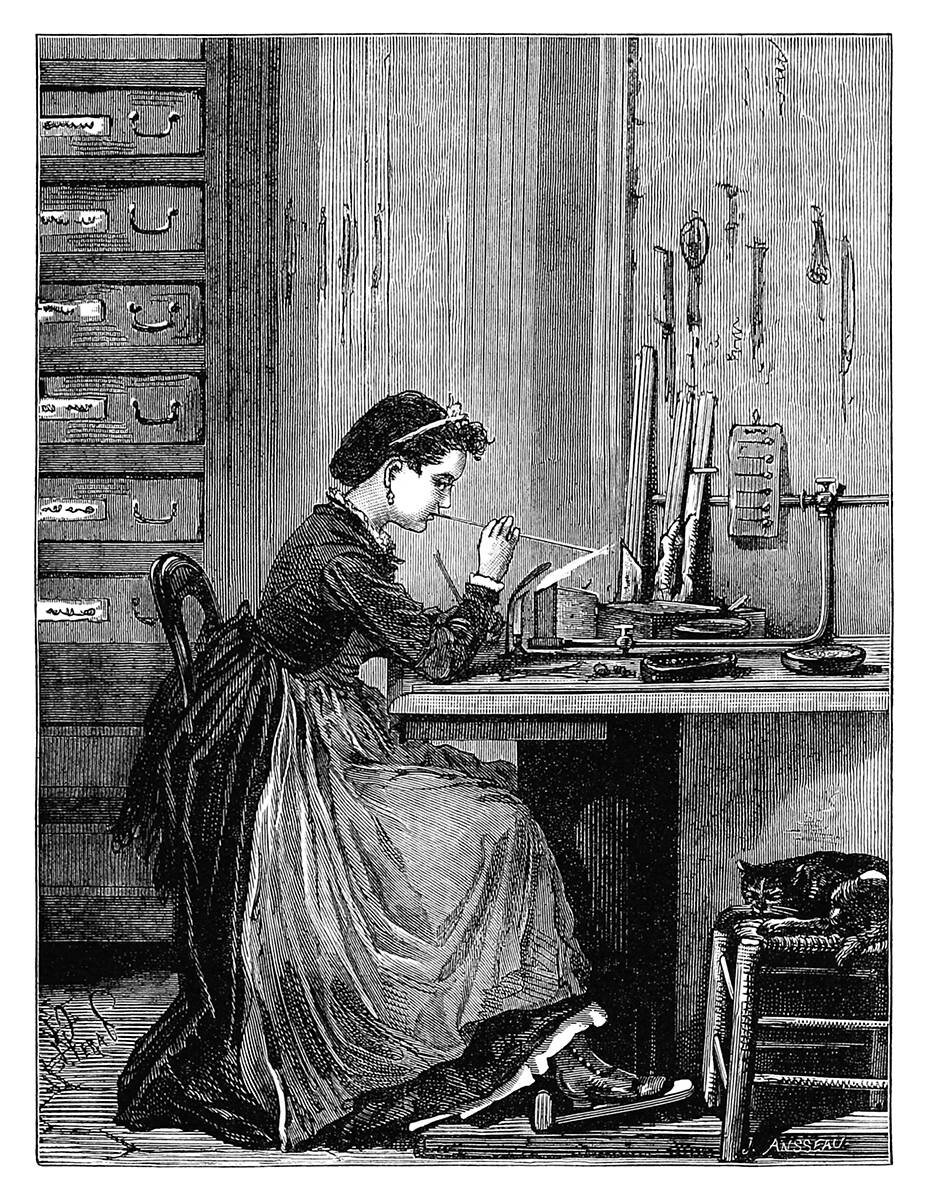

A woman is seen from the side, sitting at a work table and blowing a glass imitation pearl in the flame of a gas burner, assisted by a cat diligently napping on a nearby stool.

The author informs us that a skilled worker could make up to 300 pearls in a day. She would have been paid 2.50 francs a hundred, that is, as of the early 2020s, very approximately the equivalent of $3.90, or €3.50.

The caption reads in the original French:

Ouvrière parisienne soufflant une fausse perle.

At the Worktable

The woman is seated in profile, shoulders slightly rounded, eyes fixed on the flame. Her work table is plain, the sort that keeps its purpose in the grain and not in ornament. On the surface: a burner, glass rods, a small pile of finished beads catching the light like pale seeds. She leans forward, breath harnessed into a narrow stream, and a glass bubble begins to grow.

The flame runs blue at its heart, orange at the fringe where warmth loosens the rigid and invites shape. It makes a soft hush, a private sound that keeps a room company. Her hands move without drama, one guiding the softened strand, one steadying the air’s pressure as the glass rounds toward pearl.

There is a steadiness to her posture that comes from practice, the memory that sits in fingers. A small tilt, a half turn, a patient pause while the glow dims. She watches for that moment when heat becomes form and form cools into a gleam. The table holds the story of hours.

A narrow window would suit this work, bringing a pale strip of daylight across her lap. Dust floats, gold when it crosses the beam, pale again when it drifts into shade. The city murmurs outside; inside, the flame has the last word. She returns a finished bead to the neat dish and reaches for another length of glass.

A humble theater. No audience, one act, endless repetitions.

A cat in the margin

On a stool, a cat curls into a loop like a letter in the corner of a page. The caption says the cat assists, and sleep can be a kind of help: it wraps the workshop in the calm that lets work settle into rhythm.

A tail occasionally flicks. An ear turns toward the faint hiss of the burner. The animal does not mind the warm room or the gentle clink of beads in a shallow bowl. If anything, the tempered sounds are lullabies for whiskers and paws.

The cat adds a softness that balances the small severity of flames and tools. It makes the space human, or perhaps more than human—a place that accommodates patience and small comforts. An extra heartbeat in the margins. A witness who asks for nothing more than sun and a place to be.

Breath and Flame

Breath thickens as it meets a shorter world, the heated coil of gas and the little blue spear that licks at glass. She gathers the glass at the tip of a rod, turns it slowly—always slowly—to keep gravity from making a teardrop where a sphere should be. One learned pace, repeated.

There is an art to deciding when to blow. Too soon and the glass resists; too late and it slumps. She senses the threshold, the split second when resistance yields and volume can be counted out in a careful exhale. The bubble swells, clear and tender at first, then gaining a suggestion of weight as the material cools by degrees.

Her mouth becomes a measure. Warm air enters, shape answers back. The glow fades from orange to dull cherry, then to a colorless clarity, and the bead is almost what it will remain: an imitation of the sea’s secret labor, made here at a table with gas and patience. She removes it from the flame, cradles it with tools that refuse heat, and sets it down among its siblings.

The room smells faintly of gas and dusted glass. The day repeats this choreography.

Shaping an Imitation Pearl

To imitate is to learn the grammar of a thing. For pearls, that grammar is roundness, a surface sheen, weight that tricks the hand. The woman builds the first of these from breath and fire. The second, the gleam, will come later with coatings that give milky light to the inner wall of the bead. The third, a matter of mass, might be solved with tiny fillings or simply the presumption of the string that carries them.

For now, the sphere is her focus. She holds the softened glass to the flame until it gathers into a droplet, then she draws back and rolls it with a tiny, constant turn to coax symmetry. She blows a measured breath, a bead inflates, and at the exact right instant she smothers the flame’s claim. The surface cools to the hush of clear glass.

Every bead holds small decisions: a whisper more air, a fraction more heat, a second longer on the turn. Perfection exists as a horizon rather than a point. That, too, is part of the craft’s beauty. Each imitation pearl carries the mark of a person who balanced timing, angle, and breath.

Later, someone else may trim the ends, prepare the holes, and wash the interior with the gentle luster that gives the illusion of nacre. But the sphere begins here, a world pressed from warmth and breath in a room with a single burner and a bowl.

The Rhythm of a Day

The author tells us a skilled worker could finish up to three hundred pearls in a single day. That number—so round on the page—comes alive when laid against hours. It is not a flood; it is a current. Pearl after pearl, each one requiring attention in seconds and half minutes that accumulate into the arithmetic of effort.

There is a cadence: heat, turn, blow, cool, place. Reach, heat, turn, blow, cool, place. The body learns this rhythm and moves through it with fewer hesitations. The pauses are small: a sip of water, a glance at a clock, a cat that stretches and turns over on the stool.

Time in this room is measured in counted pieces. The bowl grows heavy, then light again when its contents are transferred to a larger dish or a tray that will carry them away. The table bears a pale ring where the burner’s heat never quite leaves.

Workdays are not identical, but they rhyme. Some beads come easily, aligning themselves with a practiced breath. Others resist—a stubborn thickness in the glass, a draft from the window that cools too quickly. She adjusts her seat, her sleeves, the idea of pace. And continues.

A day has a pulse. She finds it.

Counting Value

The line that follows the bead count is another kind of measure: pay. She would have been paid 2.50 francs for every hundred pieces completed. If three hundred are made, that becomes 7.50 francs for the day’s production. The numbers set a frame around labor’s patient work with a figure that can be written in the margin.

The arithmetic is simple, yet it carries weight. The hand that turns glass into rounds also turns hours into currency. There are rent payments within those circles, and bread, and coal for winter. There may be a ribbon for a child’s hair, a visit to a market where pears sit in small pyramids on a stall, something sweet on a Sunday.

Pay by the hundred insists on speed and steadiness. It invites a sort of counting that sits at the edge of the mind all day: how many now, how many before midday, how many after the light changes through the window. The cat moves to a warmer patch. She bends over the flame again.

Translating wages across time

The author gives a helpful comparison. In the early 2020s, 2.50 francs is roughly equivalent to $3.90 or €3.50. By that yardstick, a three-hundred-bead day would translate to about $11.70 or €10.50 for the day’s count, a figure as approximate as all such historical conversions must be.

Such conversions always compress lives into exchange rates and tables. They offer a way to feel the weight of an amount, if not the entire shape of a life built around it. Prices, rents, food, and heat obey their own eras. Yet even an approximate translation lets a present-day reader sense the narrowness of margins, the closeness between careful hands and careful household budgets.

Numbers travel poorly across years. The beads themselves travel better. They hold their light.

A Parisian Worker

Paris hums beyond the window: horses, footsteps, vendors calling, later the particular hush that falls in streets after rain. Inside, a worker whose name the caption does not say sits at her station. She is one of many who filled the city’s smaller workshops, the domestic rooms repurposed by skill and necessity into sites of production.

Her work is both solitary and connected. Solitary in the moment of breath and flame. Connected in the chain that links glassmakers, coaters, stringers, and the shops that will sell the finished strands to passersby who admire their gentle light. She belongs to a city of hands.

The room might be rented. The table might have been her mother’s. The stool belongs to a cat. The burner’s hiss has won a permanent place in the memory of these walls. A poster on the far side is curling up at the corners. She returns to the flame.

The meaning of the caption

The French caption reads: “Ouvrière parisienne soufflant une fausse perle.” Four words that place her in a city, a trade, and a moment of action. Ouvrière: a woman worker, not an abstraction but a person with tasks and hours. Parisienne: anchored, local, shaped by a city and shaping it back in long, unremarked ways. Soufflant: blowing, in the act, breath made into work. Une fausse perle: an imitation pearl, honest about artifice, honest about skill.

The phrase is economical and precise. It tells us exactly what the image shows, and leaves the rest to the eye. No name, no biography. Yet there is dignity in the naming of labor so plainly.

Beauty in the Ordinary

There is beauty in the bead’s small perfection, and also in the movements that produce it. A wrist turning, a slow inhale, the slight incline of a head to judge the cooling sheen. The scene is modest, the tools are simple, and the result is light that sits on a string and flatters every neck it graces.

Imitation does not subtract meaning. It multiplies access. Shell pearls formed in the sea are rare and carry their own histories; glass pearls carry another. They turn resourcefulness into ornament, patience into something that catches the eye. The wearers see only the glow; the workers see the steps that made it.

A cat sleeps through another hour. The city ticks forward. On the table, a tray fills with newly cooled circles that reflect the window’s pale square. The repetition itself carries a quiet elegance, the kind that invites respect rather than applause.

Sometimes a bead is imperfect. Too round, too thin, a whisper of oval in a shape that ought to be pure circle. Even those outliers have their grace notes—the story of a moment when heat or breath misbehaved, the truth that hands make things and that is why those things feel alive.

A Quiet Legacy

What remains of days like this are the beads themselves and the idea that work can be both minute and meaningful. A necklace worn to a dance, a bracelet resting on a dresser, a small glass pearl caught in the fold of a jewelry box’s velvet—these are the visible ends of a chain that began with a stool, a burner, and the focus of one Parisian worker.

There is also the memory of the room’s temperature, the particular sound of cooled beads tapped gently into a dish, the warm weight of the cat on a lap at closing time. Those details tend to slip through history’s sieve. And yet, in a quiet way, they persist. They are there whenever light finds a round surface and turns it into a soft moon.

No monuments record these hours. The caption does enough. It tells us where to look: at her hands, at the flame, at the small globe swelling at the end of a rod. The rest is supplied by attention.

Work like this builds cities. It funds meals, keeps children in shoes, and sets a table with modest pride. It also sends beauty out into the world in thousands of small, affordable circles. The gift of the ordinary is exactly that: a way of making daily life a little more luminous.

The cat opens one eye. Day wanes. She places the last bead onto the tray and turns off the flame. The quiet that follows feels like a blessing she made with her own breath.