Introduction: The Meaning of a Name at Sea

Names carry stories.

On the ocean, a ship’s name does more than identify hulls on a roster. It signals heritage, mission, and values to sailors, citizens, and rivals. A name can anchor a vessel in a wider narrative—literary, scientific, and historical—long before the keel touches water.

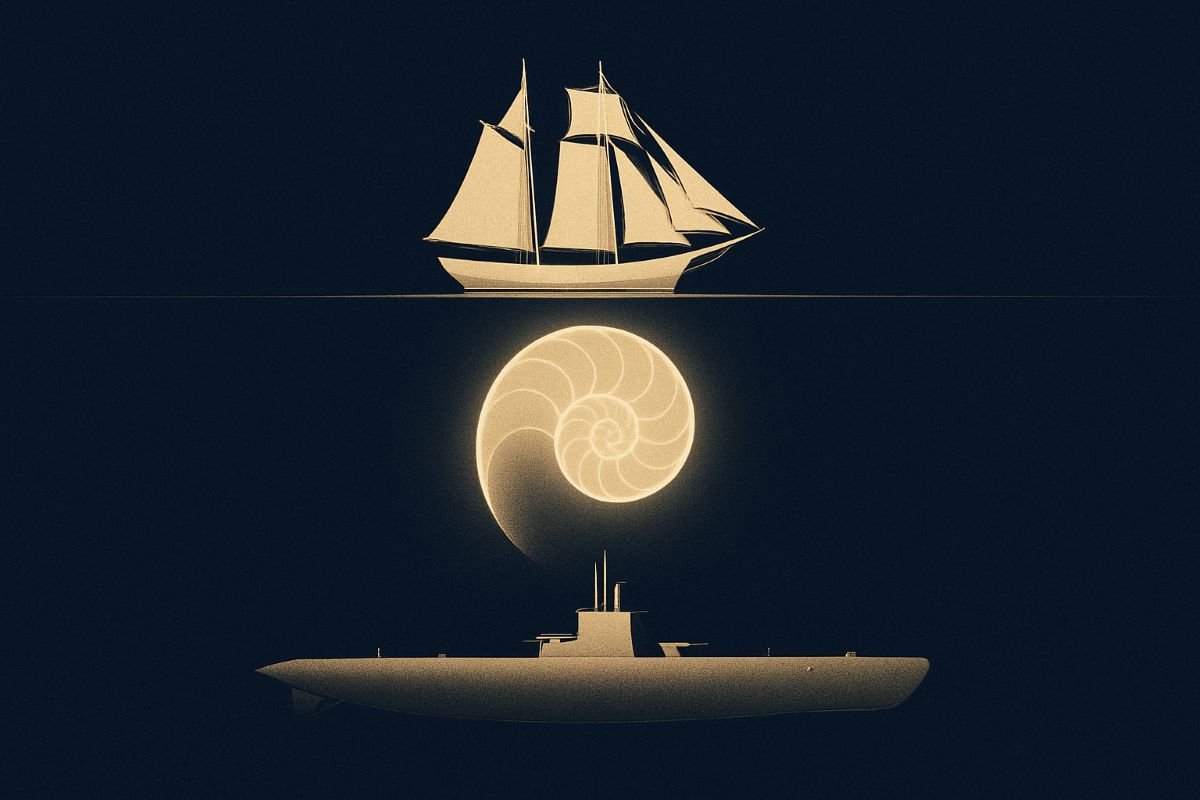

Few naval names illustrate this better than Nautilus. The choice binds a modern submarine to a classic novel, a remarkable cephalopod, and a lineage of American ships. Each strand contributes a different lesson about technology, endurance, and purpose. Together, they frame how people understand what a submarine can be.

That is the power of a well-chosen name.

Homage to Jules Verne’s Nautilus

Freedom defiance and technological wonder

Jules Verne’s 1870 novel, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, introduced readers to Captain Nemo and his vessel, Nautilus. The fictional craft was self-sufficient, electrically powered, and capable of sustained undersea travel at a time when such feats existed only on the printed page. Verne described a submarine that could circle the globe while avoiding detection, study marine life, and challenge surface powers from beneath the waves.

To readers, Nautilus stood for liberation from constraints. Nemo refused the dictates of empires and carved a hidden path across the oceans, guided by knowledge and engineering. The submarine’s salon functioned as a museum and laboratory, a symbol of science in service of exploration and autonomy.

That portrait stayed with generations of engineers and sailors. It offered a goal: build a boat that could travel far, stay down long, and rely on its own machinery and crew skill rather than the whims of wind or the need for frequent refueling. In naming a real submarine Nautilus, the U.S. Navy acknowledged that Verne’s vision defined the ideal toward which undersea warfare and oceanic research had long aspired.

Fiction inspired steel.

Science catching up to fiction

The first nuclear‑powered submarine—USS Nautilus (SSN‑571)—made that literary ideal credible. Nuclear propulsion promised an energy source that could run for months without refueling. The change was qualitative, not just quantitative. A nuclear reactor unlocked true submarine life: fast, silent travel underwater for extended periods, independent of surface oxygen.

By choosing the name Nautilus for the vessel that first demonstrated this capability, the Navy effectively said that the dream had become hardware. Verne’s imaginary craft no longer lived only in chapters and illustrations; its defining attributes—endurance, secrecy, and technical audacity—had moved into the shipyard and the fleet.

A label condensed a century of aspiration into a single word.

Nature’s Nautilus as Blueprint

Ancient lineage and logarithmic spiral

Long before engineers drew submarine pressure hulls, the ocean harbored its own “nautilus.” The living nautilus, a shelled cephalopod that has persisted for hundreds of millions of years, carries a shell shaped as a logarithmic spiral. This mathematical curve preserves shape while scaling size; each chamber grows proportionally, keeping the shell’s form consistent as the animal matures.

Inside, the shell is divided into compartments. The nautilus occupies the newest, outermost chamber while earlier chambers are sealed, with gas and liquid levels adjusted via a tube called the siphuncle. This internal architecture allows fine control of buoyancy. By altering the mixture within the chambers, the animal rises or sinks without frantic flapping or wasteful energy use.

Ancient design, modern lessons.

Pressure resistance and deep diving

The nautilus does not plunge to the greatest abyssal depths, yet it withstands significant pressure compared to surface life. The shell’s layered microstructure—alternating aragonite and organic layers—distributes stress and resists cracking. The curved geometry adds strength, much as a dome supports load through shape rather than sheer bulk.

Pressure grows by roughly one atmosphere every ten meters of depth. A shell that tolerates these forces without collapse or excessive weight offers a natural study in efficient strength. The nautilus achieves this with minimal energy: fine buoyancy control reduces the need for active swimming, conserving oxygen and resources in lean habitats.

Nature offered a template.

Parallels to submarine engineering

Engineers recognized echoes of this biology in submarine design. A pressure hull is a human-made shell, optimized to resist external forces while protecting life within. Compartmentalization and ballast systems stand in for the nautilus’s chambers and siphuncle, granting the boat precise control over buoyancy and trim. The advantages are similar: efficient vertical movement, controlled depth changes, and endurance.

Even sensor concepts rhyme. The nautilus does not see as well as some cephalopods, relying on simple pinhole-like eyes and delicate chemical and mechanical cues. Submarines likewise reduce reliance on vision underwater and use sonar and instrumentation to “feel” their environment. Both organisms—one natural, one engineered—trade raw speed for stealth, patience, and control.

The name Nautilus, then, points not only to literature but to an ancient engineer: evolution.

A Naval Tradition of the Name

USS Nautilus 1799 the schooner

The United States Navy first used the name long before nuclear power. USS Nautilus (1799) was a schooner built for the young republic’s maritime security needs. Schooners were agile vessels, suitable for coastal patrol, convoy escort, and duties that required speed and shallow draft. Assigning the name Nautilus to such a craft linked nimbleness and independence with American seafaring during a formative era.

Though worlds apart from a submarine, the schooner shared a spirit of reaching beyond known limits. Early U.S. ships carried the burden of establishing presence and credibility on the high seas. Names chosen in that period often reflected attraction to science, the natural world, or classical learning—a habit that persisted as the fleet grew.

USS Nautilus SS-168 in World War II

In the twentieth century, the name returned under the waves. USS Nautilus (SS‑168), a large cruiser submarine of the interwar period, saw extensive service in the Pacific during World War II. She supported special operations, including landing Marine Raiders during the Makin Island raid in 1942, and later ferried supplies to resistance groups. These missions demanded stealth, range, and the ability to operate far from home bases.

Such service reinforced associations between Nautilus and daring undersea work. The submarine showed how a name can accumulate meaning: from an agile schooner to a wartime boat that carried covert teams and cargo across hostile waters. By mid-century, Nautilus already meant more than a single hull. It was a thread running through missions that prized independence and reach.

Continuity matters.

The Nuclear Age Nautilus

Turning vision into reality

USS Nautilus (SSN‑571) entered the water in 1954 and signaled her new power source with a message sent in January 1955: “Underway on nuclear power.” The reactor aboard generated heat to produce steam, which drove turbines without the need to surface for oxygen. The result was sustained submerged speed and endurance previously unattainable.

This capability changed undersea operations. Submarines could now plan around the hydrodynamics of their hulls and the endurance of their crews rather than the limitations of batteries and diesel engines. Long submerged transits became normal rather than rare feats. In 1958, Nautilus steamed beneath the Arctic ice and passed under the North Pole, demonstrating a route and a method that would reshape strategy and science in polar regions.

A page from Verne had become a logbook entry.

A unified symbol for mission and identity

Why keep the name Nautilus for this first-of-its-kind vessel? Because it tied three narratives together. From literature came the ideal of a self-reliant undersea craft, roaming widely and guided by knowledge. From biology came the image of a shell designed for pressure and controlled buoyancy—a natural study in efficient survival at depth. From naval history came continuity: earlier ships had carried the name in service of patrol, special operations, and reach.

For sailors, that blend of stories contributes to day-to-day identity. Crews wear patches, paint insignia, and trade slang that reflect the ship’s name. For the public, the word Nautilus made nuclear propulsion legible. Rather than a string of technical terms, people heard a name already linked with wonder and undersea travel. Allies grasped the promise; adversaries registered the message: a new type of submarine had arrived, with endurance and stealth to match the fiction that once seemed out of reach.

Symbols reduce complexity. This one did it well.

Why Names Matter in Military Technology

How symbols shape public imagination and morale

Military hardware is technical, but public support and crew motivation are human. Names and symbols bridge that gap. A strong name distills mission aims into a single reference that can be repeated in headlines, recruitment materials, and wardroom toasts. It boosts cohesion on board by giving sailors a shared story larger than the day’s schedule.

There are practical effects, too. Programs that capture imagination tend to attract attention, which can influence funding and policy debates. A clear, evocative name helps non-specialists understand why a technology matters without parsing acronyms and specifications. Inside the service, names become shorthand for standards of performance—how a ship should handle, what missions it should lead, how its crew should carry themselves.

The right word sets expectations.

Nautilus set high ones: endurance, ingenuity, and quiet reach across the world’s oceans. Those qualities did not appear through labeling alone, yet the name helped frame them. It turned a reactor core and a steel cylinder into a character in a story people recognized, and that matters in a field where morale, clarity, and shared purpose shape outcomes.

Conclusion: The Enduring Significance of Nautilus

The choice of Nautilus shows how language can steer perception and ambition. It knits together a writer’s vision of an undersea craft, an ancient animal’s shell that manages pressure with elegance, and a naval record that pairs daring with service. The nuclear submarine that carried the name in 1954 did more than adopt a label; it accepted a standard drawn from fiction, nature, and history.

This standard endures. New submarines benefit from technologies far beyond those of the mid‑twentieth century, yet they still chase the same triad: range, stealth, and staying power. The name Nautilus continues to evoke these aims, reminding crews and citizens alike that tools are shaped by the stories we tell about them.

Names carry stories. At sea, they also carry intent.

Nautilus carries both, and it has for generations.